Levels of Innovation: Levers of Value-Add

Janne J. Korhonen

Senior Consultant

Bioss Finland

Scholarly work on innovation distinguishes incremental and radical, and, sometimes disruptive, innovation (Figure 1). Incremental innovation introduces relatively minor changes to existing products, services, processes or technology, offering savings or adding value to what already exists. Exploiting the dominant design, it benefits well-established companies. Radical innovation occurs when new products, services or technologies are introduced into an existing market or technological domain. Disruptive innovation is less about the product, service or the process, and more about value innovation: creation of altogether new business models that often combine product, process and marketing innovation. It favours the new entrants, as incumbents find it hard to copy the disruptively different approach.

Figure 1: Degrees of Innovation

Manifestation of Complexity

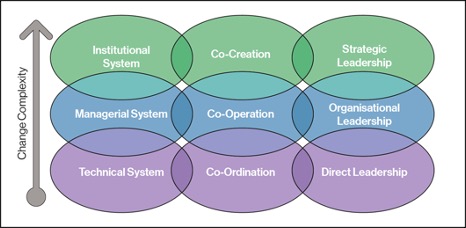

What underlies the different degrees of innovation is a universal gradation of complexity. This complexity is manifested in different scales. In the organisational scale, the classical sociological theory discerns three levels (Figure 2).

The technical system addresses the question of “how” and is concerned with “doing:” producing, selling, or providing services to a known client base. It focuses on service efficiency, operational quality and reliability, and not on the conception of new products or services. Decision-making involves accountability for existing resources. This is where most companies operate and where 95 per cent of adult human work takes place. In the scale of the team, co-ordination pertains to preserving the status quo of the technical system. This is achieved through adherence to best practices and predictable interaction patterns. Team cohesion revolves around its role applied to specific situations. Leadership is direct, and management is based on command and control.

Figure 2: Three organizational systems

The managerial system shifts away from operational business-as-usual and is concerned with added value for the future: managing continuity and change, devising new means to achieve new ends, and letting go of obsolete means and ends. The organisation as a whole is an open system that interacts with the environment in terms of information, energy, or material permeation through the system boundary.

Finally, the institutional system is the source of meaning, legitimation and higher-level support that the organisation is dependent on. This is the domain of creating new languages and new descriptions and prescriptions about the world.

In terms of team collaboration, these higher-level systems are about searching for future viability. The team critically reflects its interaction patterns and adapts to the “next practice.” The team cohesion stems from contribution within shared values and goals. On the individual level, leadership shifts away from direct leadership. Organisational leadership pertains to establishment of supporting structures and relies on delegation and trust. The time perspective is longer, the scope wider, and communication is directed more horizontally and upwards. Strategic and political leadership on the institutional level is based on nurturing of the culture through shared values that maintain coherence. Managers exhibit servant leadership that focuses on the growth and well-being of the organisation.

Levels of Innovation

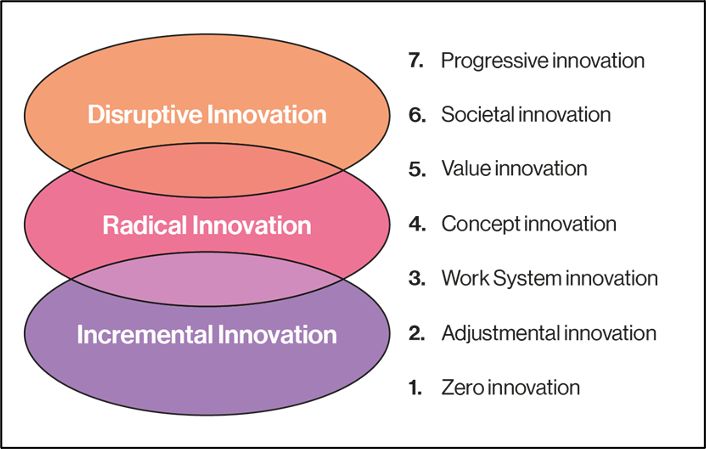

The Levels of Innovation (Figure 3) would provide a more rigorous approach and a more fine-grained vertical typology of innovation archetypes, rooted in the underlying seven Themes of Work, as defined in the Matrix of Working Relationships model1 that views work complexity in terms of nested value-adding themes. From the Themes perspective, incremental innovation would pertain coarsely to the lowest three levels of innovation, which I call zero innovation, adjustmental innovation, and work system innovation. These levels are commensurate with Themes of Work 1 through 3, respectively. In the same vein, radical innovation is in line with creating value for the future, particularly in Themes 4 and 5. I call these levels of innovation concept innovation and value innovation, respectively. Value innovation can also be a manifestation of disruptive innovation. Further, societal and progressive innovation in Themes 6 and 7 pertain to societal contribution and societal progress, respectively. They transcend the sovereign organisational entity and have their unique specific characteristics.

Figure 3: Seven Levels of Innovation

Innovation is a purposeful and systemic organisational practice to develop new ideas for economic or social value. As such, it can be seen in terms of four functions that are essential to any adaptive organism and organisation2: sensing, interpreting, deciding, and acting. In the context of innovation, sensing would pertain to the recognition of opportunities for value creation; interpreting to making sense of those opportunities; deciding on the model of decision-making; and acting to the resulting changes in work or the organisation.

In Table 1, innovation is considered against each of the four functions at each Theme of Work.

| Theme | Sensing | Interpreting | Deciding | Acting |

| 7 | Techno-economic paradigms | Appreciation of inter-connectedness and constructedness | Radical dialectical transformation | New forms of institutions, relationships and interactions |

| 6 | New-to-the-world discoveries | “Synergistic intuitions” | Muddling through | Co-evolution within the ecosystem |

| 5 | New-to-the industry business models | Individual conclusions and new theories; integrative thinking | Solution bargaining | Strategic reorientation and transformation |

| 4 | New-to-the-market/firm introductions | Hypothetico-deductive reasoning, comparison of models and contexts | Group decision making | Re-engineering of the organisation |

| 3 | Design changes to optimise market positioning | Generalising, abstracting, analytical problem-solving | Bounded rationality | Restructuring of the work system |

| 2 | Qualitative differentiation driven by new technological insights | Inductive accumulation, classification | Normative decision-making | Incremental and interdependent product and process innovation |

| 1 | Changes in style or quantitative features of existing products | Direct perception | Rules-based decisions | Efficiency improvement in the production process |

Level 1: Zero Innovation

The focus at Zero Innovation is on task excellence: how to improve the perceived quality of output, work more efficiently, and remove waste from the production process, while complying with the predefined work specifications. Innovation is driven by opportunities to make changes in style or quantitative features of existing products or services.

The opportunities for adding value are directly perceptible, and the mode of inquiry is quite concrete and factual – practical judgment within the predefined discretionary bounds. Requisite decision-making is rules-based: a master plan governs contingencies, performance expectations and individual behavior3.

The resulting change typically pertains to efficiency improvement in the production or service delivery process within the minimal critical specifications of output, resources, method, and technology4.

An example of a quantitative change within such confines would be a printer with better resolution than in its prior generation version.

Level 2: Adjustmental Innovation

Adjustmental Innovation is about qualitative differentiation of products or services from competing ones. However, it does not produce a new system effect nor resolve a new contradiction. It tends to be cost-minimising5 and driven by new technological insights.

Interpretation of opportunities for change is based on empirical inductive accumulation and classification of solution alternatives. Normative, rational decisions in a decision space of clear alternatives and utilities would be adequate6.

Innovation is about incremental and interdependent product and process innovation. The production processes and the organisation are reconfigured only marginally.

An example of a qualitative improvement at this level would be a new integrated circuit that supplants a discrete circuit for an electronic building block.

Level 3: Work System Innovation

Work System Innovations pertain to radical breakthrough changes in the design of existing products and services to readjust their market positioning7. However, the underlying product or service concept remains more or less the same. Innovation is sales-maximising8 and driven by advances in technology and demand for increased output. It pertains to product variation or new components as well as new methods of organisation, product design, and production.

The fulfilment of the needs of a certain market segment calls for analytical problem-solving and the ability to generalise and abstract a coherent Theme 3 work system. In the face of increasing complexity, the decision space cannot be comprehensively determined. As per bounded rationality9, good-enough solutions are satisfactory and information on acceptable alternatives is sequentially generated.

Level 3 innovation results in restructuring of the work system and also entails changes in the linkages to other components and systems.

An example of a sales-maximising innovation at this level would be a mountain bike that extends a familiar product to a distinct market segment.

Level 4: Concept Innovation

Concept Innovation pertains to introductions of new-to-market products or services that draw on several disciplines and/or other markets. The innovation can also be just new-to-the-firm, wherein the production or service provisioning needs to be started up. In either case, innovation at this level deals with new market offerings that target existing customer groups10. Innovation is performance-maximising11 driven by insights about new market needs and opportunities. It is aimed at unique products and product performance with a high degree of uncertainty about ultimate market potential.

To make sense of the comprehensive, evolving context, conceptual thinking is helpful in comparing models and considering different contexts: the customer’s context, the competitor’s context, the future context. The explanatory power of the model is improved through hypothetico-deductive reasoning.

As the change at this level goes beyond a contained work system, coordination and integration across units and functions is necessary, which calls for interdisciplinary synthesis and group decision making12.

Innovation at this level typically requires integration of multiple independent innovations that must work together13. Major change means re-engineering the organisation in terms of removing and creating entire work systems.

An example of a Level 4 innovation would be Nespresso that redefined the coffee consumption context at home/ the office.

Level 5: Value Innovation

Value Innovation14 is all about idiosyncratic new ways of creating value to new markets. Innovations pertain to new-to-the-industry concepts that target new customer groups and serve as potential springboards for new markets. These business model innovations often combine several product, process, and organisational innovations.

Interpretation at this level pertains to the ability to arrive at individual conclusions and even new theories as well as to integrative thinking across different frames of reference. The decision model would be that of solution bargaining15.

Level 5 innovation begets major changes in the nature of the industry, aims at changing the established value proposition, calls for intensive interaction with the external environment, and makes existing products irrelevant.

Examples of radical new-to-the-industry functions at this level would include fundamental solutions such as digital photography, the first semiconductor transistor or the first photovoltaic (solar) panel.

Level 6: Societal Innovation

The sixth level is about new-to-the world discoveries such as general purpose technologies. Such GPTs have many different uses, create many spillover effects and over time become widely used across the economy.

This level of innovation is characterised by mobility across scales, from local to global, and the ability to hold in mind multiple and conflicting ideas, emotions, and possibilities that leads to “synergistic intuitions” to discover solutions that meet everyone’s criteria16.

Decision-making, if you can call it such, in the context of multiple sovereign entities is about adjustment through incremental decisions as pertinent, as the perennial debate and co-evolution ensues.

Examples of Level 6 GPTs would include seminal discoveries such as X-rays, photovoltaic effect or semiconductivity.

Level 7: Progressive Innovation

The seventh level pertains to changes of the very techno-economic paradigms that emerge from clusters of lower level innovations. These major changes have pervasive effects throughout the economy and affect the cost structure, production and distribution throughout the system. For instance, digitalisation as a whole can be seen as a manifestation of a paradigm change of this magnitude.

This level of innovation comes with the appreciation of inter-connectedness and constructed nature of all phenomena17.

Innovation Chasm

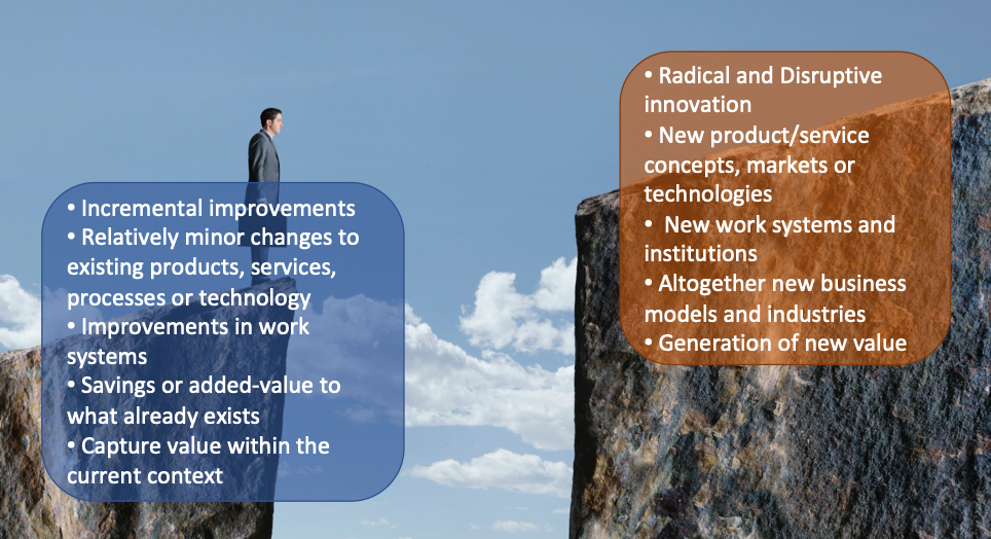

There is a marked shift in logic on the transition from the day-to-day operational work to the realm of true innovation. This ”Innovation Chasm” is characterised by a shift from incremental improvements within the current context to radical and disruptive innovation that change the context (Figure 4). Incremental changes within the technical system are confined to existing products, services, processes and technology. While their configuration, delivery and use can be changed, even substantially, the underlying assets, aims and assumptions are not challenged or changed.

This limits the value-adding potential to the optimisation of the existing work systems. Radical and disruptive innovation pertain to fundamental re-engineering and rethinking of the underlying system, which results in altogether new product/service concepts, markets or technologies as well as changes to the underlying work systems and even institutions. New value is created through new business models, and even new industries may be created as a result of breakthrough innovation.

Figure 4: The “Innovation Chasm”

In terms of the levels, the Innovation Chasm can be seen as the demarcation between the “business as usual” within the Theme 3 work systems and the Theme 4 re-engineering of the organisation to change the constitution and constellation of the set of those work systems.

Crossing this chasm is daunting, as the very premises of innovation leadership at Theme 4 and beyond are very different from the management requirements up to Theme 3 (Table 2).

Management of work systems is about preserving the status quo of existing work systems, ensuring their reliability, and improving their efficiency. The very assumption and expectation are that the context is fixed, certain and predictable. This calls for direct accountability-based leadership aimed at exploitation of the present-day affordances.

Innovation leadership, by contrast, is about renewal and replacement of the as-is work systems. The exploration of new ways of creating value requires the leader to tolerate and even embrace the uncertainty pertaining to the untried and unestablished new set of work systems. In the face of multi-system complexity, direct leadership falls short. The coordination of change efforts in the dynamic, shifting context calls for delegation and trust.

| Aspect | Management of Work Systems (Theme 3) | Innovation Leadership(Theme 4) |

| Cognitive Logic | Constitution and sustainment of systems | Construction and coordination of systems |

| Epistemic Stance | Assumption of certainty | Toleration of uncertainty |

| Motivation | Exploitation of present-day affordances | Exploration of future outcomes |

| Leadership style | Direct leadership, position-based authority | Delegation, trust |

Applying the Theme 3 management logic to Theme 4+ challenges will be utterly unhealthy. Ignoring the need to realign the organisation with the changing context, tinkering with seeming improvements within the confines of the present-day work systems, and keeping even tighter reins on them are conducive only to digging the organisation into a deeper hole. A shifting context calls for radical innovations and true innovation leadership that is open to the exploration of new value and respective transformation of the organisation.

Footnotes

Stamp, G. (1990): A Matrix of Working Relationships. Bioss.

2 Cf. Haeckel, S. (1999). Adaptive Enterprise: Creating and Leading Sense-and-Respond Organizations. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

3 Nutt, P. C. (1976). “Models for decision making in organizations and some contextual variables which stipulate optimal use.” Academy of Management Review 1, no. 2: 84-98.

4 Cf. Hoebeke, L. (1994). Making Work Systems Better: A Practitioner’s Reflections. John Wiley & Sons.

5 Sensu Utterback, J. M. and Abernathy, W. J. (1975). “A dynamic model of process and product innovation.” Omega 3, no. 6, 639-656.

6 Nutt (1976), op.cit.

7 Cf. Van Vrekhem, F. (2015). The Disruptive Competence: The Journey to a Sustainable Business, from Matter to Meaning. Kalmthout, BE: Compact Publishing.

8 Sensu Utterback and Abernathy (1975), op. cit.

9 Simon, H. A. (1955). “A Behavioral Model of Rational Choice.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 69, no. 1: 99–188.

10 Cf. Barthel et al. (2020). “Embedding Digital Innovations in Organizations: A Typology for Digital Innovation Units,” Wirtschaftsinformatik (Zentrale Tracks), 15th International Conference on Wirtschaftsinformatik, Potsdam, Germany, March 8–11, pp. 780-795.

11 Sensu Utterback and Abernathy (1975), op. cit.

2 Nutt (1976), op. cit.

13 Slaughter, E. S. (1998). “Models of Construction Innovation.” Journal of Construction Engineering and Management 124, no. 3 (May/June): 226-231.

14 Cf. Kim, W.C., and R. Mauborgne. (1998). “Value innovation: the strategic logic of high growth.” IEEE Engineering Management Review 26, no. 2: 8–16.

15 Nutt (1976), op. cit.

16 Joiner, B. and Josephs, S. (2007). Leadership Agility: Five Levels of Mastery for Anticipating and Initiating Change, Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, CA.

17 Cook-Greuter, S. (2005) “Ego Development: Nine Levels of Increasing Embrace”.

© 2022 BIOSS ™. All Rights Reserved.